By Carolina Lee and Liz Thompson

The HESTA Divest campaign was recently approached for an interview by Daniel Hannington-Pinto, a PhD candidate, as part of his research on social and moral campaigning by Australian trade unions. The campaign team prepared the following response which covers the following points:

- Research by the xborderops network on union involvement in the detention industry as the impetus for the campaign. We note that no other industry super fund has divested from Broadspectrum (now owned by Ferrovial) in the 2 years since HESTA’s divestment, in this fifth year since the re-opening of the detention centres on Manus Island and Nauru.

- With limited exceptions, trade union leaders did not support the campaign and some actively opposed efforts to disrupt the detention industry. Additionally key ‘activist’ parts of the union sector and left organisations regularly obfuscated unions’ material interest in detention, which we identified as arising from an investment in nationalist and electoral projects.

- HESTA Divest was an example of how anti-border politics can win if we act outside the terms of left nationalist politics. We identified our role in detention supply chains, built networks and coordinated with each other to organise meaningful pressure against HESTA by clearly drawing the link between HESTA and detention. A small group of people made HESTA’s detention investment untenable by shifting the risks of detention back onto profiteers.

The following material was prepared in response to research questions by Daniel Hannington-Pinto, a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne. Daniel’s research explores the social and moral campaigning of Australian trade unions, with the HESTA Divest campaign comprising one of his case studies. If you were involved in the campaign and would like to contribute, please contact Daniel at danielhp@student.unimelb.edu.au

- What was the catalyst for the HESTA Divest campaign and what form did initial action take? Who was involved in the earliest stages?

The HESTA Divest campaign emerged from the work, research and analysis of Cross Border Operational Matters (xborderops).[1] One of the ways that the network aims to change Australian border policies and end mandatory detention is by supporting action against detention industry supply chains such as superannuation fund investments. Prior to HESTA Divest the network had provided critical support to the successful boycott campaign to end the sponsorship of the Biennale of Sydney by Transfield Services (now Broadspectrum). xborderops has also organised and supported other boycott and divestment campaigns against organisations associated with the detention industry.[2]

HESTA’s links to mandatory detention were first raised by xborderops in January 2014 when the fund was revealed to be one of many super funds that employed Allan Gray, then-largest shareholder in Transfield Services, as an investment manager.[3] In February and March during the period of the Sydney Biennale boycott campaign, HESTA members publicly began to call for HESTA’s divestment from Transfield.[4] In the wake of the Sydney Biennale boycott in March, the National Executive of the Australian Services Union (ASU) adopted a resolution calling for HESTA’s divestment, a move which had been initiated by the ASU NSW & ACT branch.[5]

Momentum stalled, however, as other union and employer groups represented on the HESTA Board remained silent over the fund’s investments in detention, and no further public statements were released by the ASU on this issue. Throughout 2014 HESTA continued to increase its investment in Transfield Services, reaching the threshold of a substantial shareholder status (a more than 5% stake) in December 2014.[6] This was despite the ASU National Executive motion, the deteriorating situation for detainees on Manus Island and Nauru, and the likely concern held by HESTA members, as health and community sector workers, for the welfare of asylum seekers and refugees. Given all of this, members of the xborderops network identified HESTA as a strategic target for a detention divestment campaign.

Initial action for the campaign took the form of Sydney and Melbourne-based xborder network members developing resources to explain the link between HESTA and the detention industry. We also formed connections with health and community services workers in Brisbane who were highly concerned with the involvement of their industry super fund in asylum detention. This group of people decided to raise awareness about HESTA’s investments at the nation-wide Palm Sunday rallies in April 2015, which have focused on refugee issues in the last few years.

The HESTA Divest campaign was publicly launched just prior to the Palm Sunday rallies in the form of the campaign website,[7] which included briefings and other resources for HESTA and union members, and the Facebook page.[8] We also began using #HESTADivest on Twitter. The campaign team made a callout for volunteers to distribute campaign leaflets at the Palm Sunday rallies and there were small but committed contingents, mostly in HESTA Divest T-shirts we had created, at the Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne and Perth rallies.

The campaign team also contacted Palm Sunday rally organisers and speakers to see if they would promote the issues. Dr Sue Wareham, from the Medical Association for the Prevention of War, mentioned the campaign during her speech at the Sydney rally. On the Facebook event page for the Sydney rally, individuals involved in the campaign also raised concerns with the participation of unions such as the NSW Nurses and Midwives Association (NSW NMA) and the ASU given the roles of the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) and the ASU on the HESTA Board.[9]

In the early stages of the campaign, the team also received some advice from the manager of an ethical investment business based in Sydney through a team member’s personal connection. The campaign worked with the business manager to draft a series of questions to pose to HESTA regarding the scope of their investments in Transfield Services and other detention industry contractors, and their Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) position on detention investment. These questions were sent by the business to HESTA in mid-March 2015, and the business followed up with HESTA at various points throughout the campaign.

The business also contacted numerous super and investment funds to determine their position on detention investments, and assisted to raise the ESG concerns and awareness of super fund campaigning against Transfield Services in the investment industry. Through this contact we are aware that a small super fund decided to exclude Transfield investments on ethical grounds, however this position only became public in the wake of HESTA’s divestment.

- How many members of the HESTA Divest campaign were connected to unions? Which unions were they from, and what roles did they hold in them?

No campaign members were formally connected to unions in terms of being union organisers, delegates or staff. Some of the health and community sector members that became involved in the campaign were also members of the ASU. Other campaign members were members of the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU), and some had previously worked in unions, including in the United Voice. No core campaign members were active in their unions.

- Were the skillsets or networks of these unionists particularly important in progressing the campaign or in addressing any limitations as it progressed?

Please see Questions 4 and 5 for an explanation of the way that the skillsets, networks and knowledge within the campaign team were critical to progressing the campaign. One of the limitations we experienced was the lack of support from certain sections of the union and refugee sectors – see Questions 9 and 4. In terms of addressing this, the campaign team anticipated this as we are aware of the record of trade union and left investment in nationalist and electoral projects,[10] and that this would limit support for detention divestment from certain parts of the union sector and the left. As such we were not surprised or deflated by these developments, and continued to focus on the HESTA constituents that we believed would have the disposition to act, including rank-and-file union members.

- What relationships did HESTA Divest develop with other social movement partners, NGOs, or trade unions, and how did this coalition-building actually occur (ie. were connections made following your approaches, approaches from the external parties, or a combination of the two)?

Campaign team members made a concerted attempt to reach out to union contacts amongst our networks in the initial stages of the campaign. Please see Question 9 for an overview of our attempts to gain support within unions. In summary most of our union contacts were privately sympathetic, however most of the support we received ultimately did not come from within unions. The campaign ask received no public support from the leadership of any union apart from the ANMF – see Question 8.

In addition to seeking trade union allies, we also approached other groups and individuals whom we believed may be sympathetic such as health, community, refugee advocacy and faith-based groups. We initially contacted groups and individuals through our personal networks. When the campaign began to develop a public profile in its later stages, various group representatives also contacted HESTA Divest through our campaign email address and social media (for example, a Red Cross Sydney representative).

The success of our coalition-building varied. Apart from the limited trade union support we received as outlined in Question 9, some refugee advocacy groups were not interested in the campaign, and some actively hostile to the campaign. These groups tended to be dominated by socialist group members who are generally uncritical of the nationalism of trade unions, and are focussed on government targets and dismissed our campaign as ‘symbolic’. Many of these groups eventually jumped on board with the campaign as it gained publicity, however some state Refugee Action Collective groups in particular continued to be hostile to the campaign.

As the campaign gained momentum throughout May and June 2015 most of the people that got involved were health or community sector workers, and individuals interested in refugee advocacy and supportive of divestment. The campaign also received support from the SEARCH Foundation, which hosted a campaign meeting. We also received some support through faith-based connections – for example a key campaign member was involved in a Sydney church and some of these church members were the earliest supporters of the campaign.

- In what way/s did such relationships help the campaign?

In general pre-existing relationships and connections were critical to the formation and success of the HESTA Divest campaign. As should be clear by now the campaign was a coordinated grassroots network effort that received little institutional support, and in fact a fair amount of hostility from certain sections of the union and refugee sectors.

As outlined above the campaign initially formed out of the network around xborderops. Many of us had previously worked together in different spheres and prior to HESTA Divest, most of us had also worked together as xborderops on the Biennale of Sydney boycott. The knowledge and skills mix within xborderops were crucial factors in the campaign’s pertinent financial and political analysis, our communications strategy and the resourcing of this, and the organising that led to our campaign victory.

As has also been outlined the campaign team initially sought support through our personal networks, prioritising contact based on the constituent groups that we believed would be most sympathetic. This was a strategic decision based on our resources, and also one that reflected our political analysis. That is, that as people living in Australia, we are already implicated in supply chains to the refugee detention industry – super fund investment is one example of this. Apart from running specific targeted campaigns, one of the broader goals of the xborderops network has been to identify these supply chains and provide resources for people to take effective collective action to use their position to disrupt and break these supply chains.

- Apart from the informative and engaging website, was the campaign promoted in other ways (eg. in the media)? If so, who represented the campaign and were any unionists involved in this process?

The campaign was primarily promoted via Facebook and Twitter. Campaign members used social media to identify opportunities to exert and focus pressure on HESTA Board Directors, particularly Union Directors, including by commenting on news items regarding the horrific nature of the Manus Island and Nauru detention centres.

On Twitter the campaign was heavily promoted via the xborderops account, which is followed by many anti-border groups, activists and journalists in and outside of Australia. Many people associated the campaign with xborderops and the campaign itself was clearly linked with xborderops, particularly insofar as it cited and drew heavily upon xborderops’ research and analysis.

In terms of representation, the campaign represented itself as a network of concerned health and community services workers and anti-detention advocates. In particular the health and community services contingent in Brisbane played a key role in the momentum of the campaign – their experiences, anger, connections and work played a key role in the development of the campaign, and in promoting the campaign outside of the typical groups associated with the ‘refugee advocacy’ movement.

Community services workers also played a key role in a significant action taken by the campaign at the 2015 HESTA Community Sector Awards, held at Sydney Town Hall in June 2015. Wearing our bright green T-shirts, campaign team members held large banners on the Town Hall steps and handed out information to event attendees regarding our call for divestment. We had also booked a table for eight inside the event, which comprised four HESTA members, one ASU member and six people that work or have recently worked in the community services sector. During the evening campaign members primarily introducing themselves as community sector workers and HESTA members, spoke about the campaign with key HESTA representatives such as Debby Blakey, CEO, and Angela Emslie, Chair of the Board. We also spoke with key community sector leaders, including from employer groups on the HESTA Board such as the Australian Council of Social Service.

- Regarding the resources you offered on the website for union members and officials (the sample member’s letter to HESTA, the sample union divestment motion, the campaign poster, and the campaign leaflet), were these developed in conjunction with unionists or were the campaign representatives who developed them union members themselves?

Many campaign team members were themselves union members or had previously been active in unions, and were experienced with developing motions and resources.

Some of the resources were developed from xborderops resources for the campaign calling on UniSuper to divest from detention. (This campaign was initiated and largely driven by xborderops network members, some of whom are members of UniSuper and the NTEU, prior to the HESTA Divest campaign,[11] and people’s experiences with this campaign influenced our approach to HESTA as outlined in Question 9.)

- a) Also, do you have any data on how many times these resources were downloaded or printed off from the website?

Unfortunately this data is unavailable.

We are aware that numerous HESTA members utilised the campaign resources when contacting HESTA, as they forwarded us a copy of their correspondence to HESTA along with HESTA’s responses.

Regarding the ASU Brisbane branch motion condemning the Border Force Act (see Question 9), a campaign team member was contacted to assist with the wording of this regarding the HESTA piece.

- Were there certain unions (and state/territory branches therein) that were especially active in supporting the campaign?

During the campaign the only union that supported the campaign ask was the ANMF, in particular the Victorian branch. At the branch Delegates’ Conference in mid-June 2015, the conference passed a motion requesting ANMF (Vic Branch) to lobby the HESTA and First State Super superannuation funds to “divest themselves of investments in organisations whose business interests directly or indirectly breach the human rights of those seeking asylum”.[12]

Subsequently on 27 July 2015, the ANMF posted the following on their Facebook page: “We have raised ANMF (Vic Branch) members’ deep concerns regarding super fund investment in Transfield Services. Transfield Services holds contracts with the Australian Government to run both the Manus Island and Nauru offshore detention facilities.

We are pleased to advise that First State Super has no shareholdings in Transfield Services, meaning none of the First State Super’s members’ money is invested in this company.

We are hoping for a similar response from Hesta in the coming weeks.”[13]

After HESTA’s divestment, the ANMF (Vic Branch) released a statement in support of HESTA’s decision on their website.[14]

The ASU National Office issued a similar statement in August 2015.[15] This statement provided that the ASU had been involved in discussions with HESTA since the National Executive motion in March 2014 via National Secretary David Smith. (However as noted above, as far as the campaign team is aware no sections of the ASU released public statements on HESTA’s investments in Transfield Services between March 2014 and August 2015.)

Individual ASU members provided active support to the campaign. In approximately May 2015, a campaign team member in Sydney organised for their ASU branch to pass a motion calling on the ASU to pressure HESTA to divest.

In June 2015 an ASU member in Brisbane attempted to pass a branch motion condemning the passing of the Border Force Act, which also sought an update on HESTA’s investments in Transfield and supported the call for urgent divestment. (We have not been able to confirm whether or not this motion was passed.)

- Were you aware of any dynamics of contestation between different levels of those unions, with regards to support for, or opposition to, the calls for divestment? In other words, did the public position/statements of any union leaders contradict those of their rank-and-file or delegates/activists?

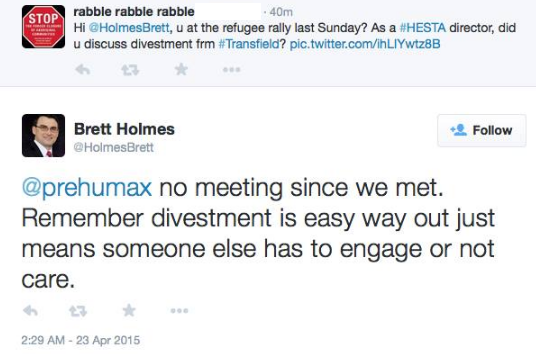

The support for the campaign ask from sections of the ANMF, particularly the Victorian branch, has been outlined in Question 8. This is in contrast to the position taken by Brett Holmes, General Secretary of the NSW NMA and then-Director for the ANMF on the HESTA Board, in April 2015. In the early stages of the campaign following the Palm Sunday rallies, a campaign member had the below Twitter exchange with Brett Holmes, who has since deleted the tweet:

In addition to reaching out to rank-and-file members and delegates/activists amongst our networks as has been described elsewhere, campaign members also contacted union organisers and staff to seek support for the campaign. Below is a sample of our contact:

- An ASU organiser in the NSW & ACT Branch provided that they understood the ASU Director on the HESTA Board was “actively advocating” on Transfield divestment inside the Board, following the National Executive motion in 2014. The organiser also provided that the ASU had put out communications to members suggesting they speak with HESTA about ethical investment options if they are concerned about the ethics of the investment of their super. The campaign team requested but was not provided with a copy of these communications. We also noted that calling on union members to speak with HESTA about ethical investment options is not the same as calling on HESTA to divest; we were also aware that this reflected the specifics of the ASU National Executive motion which, whilst calling for divestment, also undertook for ASU to provide its members with “information on how to take individual action to ensure their money is not being invested in Transfield by exercising investment choice within the fund.”

- An ASU staff member in Sydney indicated that they had understood HESTA had already divested, however realised this was not the case when pressed. They and a Sydney organiser provided that the campaign would need to mobilise union members as opposed to staff in order to pressure State and National Secretaries and leaders for action.

- A HSU organiser in Sydney provided that for the HSU to support the campaign issue, it would need to be linked with another that affected HSU members’ employment, such as the privatisation of hospitals in Western Australia by Serco. People we contacted with links to the ANMF made similar comments.

- Please see Question 10 regarding our contact with ex-United Voice staff members.

To summarise the response of the union organisers and staff whom the campaign team spoke with, regarding the ASU this would be to say that the ASU was already acting on this issue. Generally union organisers suggested that it would be difficult to mobilise union members on divestment, in part because the role of unions in industry super funds is not widely known amongst union members. Regarding the United Voice it was said that they would be difficult to mobilise due to their membership base including detention centre security guards.

In the campaign team’s analysis, these responses served to mask and minimise the level of union inaction on industry super fund detention investments following the ASU National Executive motion in March 2014. For example our experience with union members we connected with was not that there was a lack of understanding of the issues or buy-in – to the contrary they were highly motivated around this issue. Many had a visceral reaction of horror upon realising that their retirement savings were invested in the Manus Island and Nauru detention centres.

The fact that union officials we spoke with did not see divestment as an issue of priority or traction to us indicated a lack of political interest within unions in detention divestment. In our analysis this was largely due to unions’ material interest in detention via industry super fund investments, and detention worker union membership fees in the case of the United Voice. Union officials also seemed reluctant to shine a spotlight on the fact that unionists are actively investing in detention centres, which is antithetical to the progressive face that unions present.

Unions could also afford to ignore our campaign as we were perceived to be small and marginal. Indeed we would agree this was the case until our successful intervention at the 2015 HESTA Community Sector Awards turned the issue into one that HESTA and Board representatives could no longer afford to ignore for the sake of their brands and reputations.

Furthermore it is clear that some union leaders are opposed to divestment in favour of “better” management of detention investments. In addition to the above comment by Brett Holmes, during a Lateline report in October 2015 on super fund divestment from Transfield Services, Dave Oliver, then-ACTU Secretary, argued in favour of using the power of super funds and investments to change the behaviour of companies such as Transfield, whilst delivering a good return for members.[16]

We also think it is worth noting that one of the ways that Transfield sought to minimise the damage following HESTA’s divestment was to seek to offer tours of the Manus Island and Nauru detention centres to industry super funds. The Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (CSI), which Board includes industry super fund representatives, did not oppose this proposal and the CSI chief executive stated that site visits help to improve transparency.[17] In our view, this position contributed to stalling the momentum behind detention divestment in the wake of HESTA’s decision.

We also note that no trade union spoke out against Transfield’s proposal, and that since HESTA’s divestment, no other industry super funds have committed to divestment, despite concerns being raised about the UniSuper and CBUS detention investments in particular.[18] Since the supportive statements from the ANMF and ASU regarding HESTA’s divestment, we are also not aware of any union support for divestment apart from the NTEU’s involvement in the University of Newcastle Students Against Detention campaign against the University’s contract with Broadspectrum,[19] however we were not involved in this successful campaign so are unable to comment on the details of this.

As has been flagged previously, the campaign team also drew our analysis of union inaction on divestment from our experiences in the campaign for UniSuper’s divestment from Transfield Services. Through this campaign, the majority of NTEU organisers and staff we spoke with made it clear that they preferred to maintain a sharp distinction between the ‘material or economic’ and the ‘political’ – officials preferred to keep their involvement in refugee issues to supporting campus refugee groups, and many repeatedly refused to provide any meaningful support to the UniSuper divestment campaign. While ordinary NTEU members were horrified to discover that their compulsorily acquired superannuation money was invested in mandatory detention (as were ANMF and ASU members), and approached us to be involved in the campaign, many union officials seemed terrified to mobilise members around this point of leverage: they seemed to believe that you could only mobilise members if they could feel good about themselves and their unions, whereas pointing out union investments in mandatory detention was clearly antithetical to this. We also noted that Grahame McCulloch, NTEU General Secretary, who sits on the UniSuper Board, wrote an article in March 2015 implying that UniSuper had divested from Transfield Services[20] – this regularly produced confusion on UniSuper’s investment throughout the course of the UniSuper Divest campaign.

Whilst we were not unaware that union officials may be uncomfortable with a campaign which pointed out inconvenient truths about the gap between progressive union policy passed at national conferences and the actual action taken by unions on issues such as superannuation investment, we did not expect the hostility towards divestment from some NTEU officials in particular, many of whom considered themselves to be on the left of the union.

- Following on from the last question, did any unions generally prove more difficult to engage? I’m thinking here perhaps of those such as United Voice, who had members working in the very industry in which Transfield was operating (for instance, in security roles on Manus and Nauru).

Regarding the United Voice, we primarily spoke with contacts who had previously been employed by the union as staff members. We sensed that it would be difficult to obtain support from the United Voice leadership, despite the union’s general image as a progressive union, due to its record of active and successful unionisation of detention security guards, vigorous industrial campaigning on behalf of detention centre staff, calls for reopening onshore detention centres, and increasing silence on immigration detention in the last few years. We were also aware of heavy union density in detention centres in which we had particularly strong contacts with detainees, including those transferred from offshore and who, throughout the HESTA Divest campaign period, faced the ongoing threat of violent deportations to offshore centres. In July 2015, the campaign team also noted that sections of United Voice were reported as having helped to defeat a motion that would rule out ‘turnbacks’ as a policy option for the Australian Labor Party at the party’s national conference.

Noting the above and our limited resources, HESTA Divest did not prioritise contacting United Voice members during the course of the campaign.

- Did the campaign receive any public pushback from stakeholders (eg. members of HESTA or the unions, or the media) and, if needed, how did you respond?

During the campaign the only public pushback from stakeholders was from some refugee advocacy groups, as outlined in Question 4. The campaign team responded by making the case for divestment in the political economy of the asylum detention industry, and by otherwise focussing on mobilising other campaign constituents.

Whilst there was no explicit pushback from unions apart from the tweet by Brett Holmes, most of our attempted contact with union leaders was ignored. As discussed in Question 9, in our view unions showed little political appetite in divestment and could ignore our campaign for the most part, until the end of June 2015 after both the ANMF Victorian Branch motion and our action at the HESTA Community Sector Awards.

It is worth noting that when HESTA divested, the pushback from the Australian Government and large companies was largely directed towards the perceived role of trade unions in the campaign, and union representation on industry super funds. This was not a new source of contention amongst conservatives and employer groups, however there were renewed and vigorous calls to remove or minimise union representation on industry super funds in the wake of HESTA’s decision. We attempted to clarify the minimal role of the leadership of trade unions, and present our perspective on the campaign in an article in New Matilda published on 25 August 2015: ‘HESTA divests: Disrupting The Supply Chains Of Mandatory Detention’.

- Did the campaign seek out, or receive, support from any politicians or parties? I’m guessing – because of its bipartisan approach to mandatory detention – that the ALP didn’t actively back it, but how about any Greens, Independents, or other state or federal parliamentarians?

The campaign did not seek out, or receive, support from any politicians or parties. Our focus was on mobilising HESTA constituents and supporting them to act from their position of power. None of the people that got involved in the campaign were active members of political parties, and so we did not turn our resources towards these.

- Looking back at its success in achieving its stated outcome, what would you consider the campaign’s greatest strength/s?

One of the campaign’s greatest strengths was to demonstrate the ability of boycott and divestment campaigns to disrupt the political economy of the detention industry, particularly in the face of entrenched bipartisan support for mandatory detention. We succeeded in broadening people’s understanding of the detention industry: rather than seeing this as “offshore” and a fixed manifestation of government policy, we sought to show how it is made up of a series of contracts that calculates, assigns and manages the risks of detention, converting risk into maximum value for detention profiteers.[21] We also demonstrated that everyday economic decisions, such as where super is invested, contribute to the financial, cultural and philanthropic supply chains of detention. The HESTA Divest campaign, then, showed how a relatively small group of people can coordinate with each other to disrupt profiteers’ calculations, and render involvement in detention costly, unpredictable and ultimately financially ruinous for detention companies.[22]

Our analysis meant that we designed the campaign on the basis of locating and acting from our own roles/positions of power within detention supply chains. We focussed our available resources on mobilising the people who were in the right position and disposition to act, and who would do the necessary work without getting caught up in trying to convince everyone else to act before they acted themselves. We consider that another of the campaign’s strengths was the way that it broke down the issues and required action in a way that allowed people without much of a background in political economy or organising to pick up and use the resources to pressure HESTA effectively. We are aware that HESTA received messages from ordinary members from all over the country and many of the people we worked with, particularly in Brisbane, did the work of leafleting and talking to people at work in the face of a total lack of support from the established refugee activist groups, and none from their unions.

Indeed we think another key campaign strength was to show how anti-border politics can win if it is done outside the terms of left nationalist politics. Rather than working with a tunnel vision on mass rallies and industrial action, traditionally conceived as the work of trade unions, we brought an analysis of supply chains to the detention industry and identified the relevant players, including trade unions. Our commitment to cross-border solidarity meant that we were not willing to remain silent over union complicity in funding detention, even if this was outside the usual terms of left nationalist politics. We anticipated union resistance and the criticism of some sections of the left based on our targeting of unions, however we refused to stay silent and felt confident in the belief that we did not need to wait for the support of union or left nationalist leaders to get things done.

Finally we believe another key strength of the campaign was being unequivocal about the need for divestment, including not letting unions or union apologists fudge and get away with union investments in detention, whilst taking on the appearance of action, for example by passing motions opposing detention and supporting Palm Sunday rallies. We were clear about what was at stake – whether or not HESTA and its associated organisations will continue to invest and seek to profit from asylum detention. By being clear about the issues and mobilising the right type of pressure, we believe the campaign played a key role in forcing the HESTA Board to re-evaluate the risk and value of detention investments against the damage to their own organisations’ brand and reputation.

- And finally, what lessons do you think HESTA Divest could pass on to campaigns calling for divestment of similar companies, or those in other industries such as the processing of fossil fuels?

HESTA Divest has already been approached to provide advice and support to other campaign groups such as Healthy Futures, which is currently campaigning for HESTA and First State Super to divest from fossil fuels.[23]

We would reiterate the strategic impact of ‘brand damage’ – to the company and associated groups – and focussing on mobilising and supporting the relevant constituents. More broadly we would pass on the questions raised above of looking at how profiteers calculate and manage the risk within damaging industries, and seeing how we can disrupt these and shift risk back onto decision makers. We encourage people to research and develop their own responses and strategies, depending on the particular contracts and industries, and to be unequivocal about the parties responsible.

[1] https://xborderoperationalmatters.wordpress.com/

[2] See http://divestfromdetention.com/

[3] https://xborderoperationalmatters.wordpress.com/2014/01/30/internment-infrastructure/

[4] https://xborderoperationalmatters.wordpress.com/2014/02/04/is-your-superannuation-invested-in-scott-morrisons-refugee-policy-a-response/

[5] http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/australian-services-union-calls-on-hesta-to-divest-funds-from-transfield-services-over-its-links-to-manus-island-20140312-34mle.html

[6] http://hestadivest.net/about.html#fn2

[8] https://www.facebook.com/hestadivest

[9] https://www.facebook.com/events/1416537418647398/permalink/1433795923588214/

[10] https://xborderoperationalmatters.wordpress.com/2015/07/22/a-gentle-reminder-unions-are-part-of-the-detention-industry/; https://xborderoperationalmatters.wordpress.com/2014/02/28/thompson-re-rally/

[11] https://xborderoperationalmatters.wordpress.com/2015/10/02/unisuper-nteu-update/

[12] https://twitter.com/TaraNipe/status/613894311483064320

[13] https://www.facebook.com/RespectOurWork/photos/a.224201757639566.54688.216647058395036/912249078834827/?type=1&theater (link no longer active)

[14] https://www.anmfvic.asn.au/news-and-publications/news/2015/08/19/hesta-divests-from-transfield-services

[15] http://www.asu.asn.au/news/categories/super/150819-asu-supports-hesta-divestment-transfield

[16] http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2015/s4325581.htm

[17] http://www.smh.com.au/business/transfield-services-to-tackle-governance-risks-after-net-profit-falls-8pc-20150825-gj7b7a

[18] For example, see http://unisuperdivest.net/

[19] https://www.facebook.com/search/top/?q=Students%20Against%20Detention%20UoN

[20] https://xborderoperationalmatters.wordpress.com/2015/03/25/nteu-statement-on-unisuper-investments-in-detention-highered/

[21] See https://thenewinquiry.com/cross-border-operations/

[22] https://newmatilda.com/2015/09/10/are-divestment-campaigns-calls-nicer-cages-ethical-carnage-and-cleaner-coal/#sthash.PEuPELwt.dpuf